The first in a two-part series on advanced biofuels.

In 2008, a group of airlines came to Boeing Co., the world’s largest aerospace company, with a big problem. At that point, the United States, under President Obama, was instituting policies to fight climate change. One of them involved cutting emissions from jet fuel.

A year earlier, bipartisan support from Congress had given the new administration what seemed to be a powerful new tool to do it, a law calling for “advanced biofuels.” It promised to be a new category of fuels that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50 percent compared with petroleum-based fuels. It was aimed at the transportation sector, second to only electricity generation as the biggest emitters of CO2.

At the time, solar and wind power were already beginning to reduce power plant emissions, and the general assumption was that within 10 years the auto industry would begin to reduce its share of the transportation problem by producing electric cars. But the airlines worried that there was no way to use solar and wind to power commercial airplanes. Electric airliners weren’t on the drawing boards.

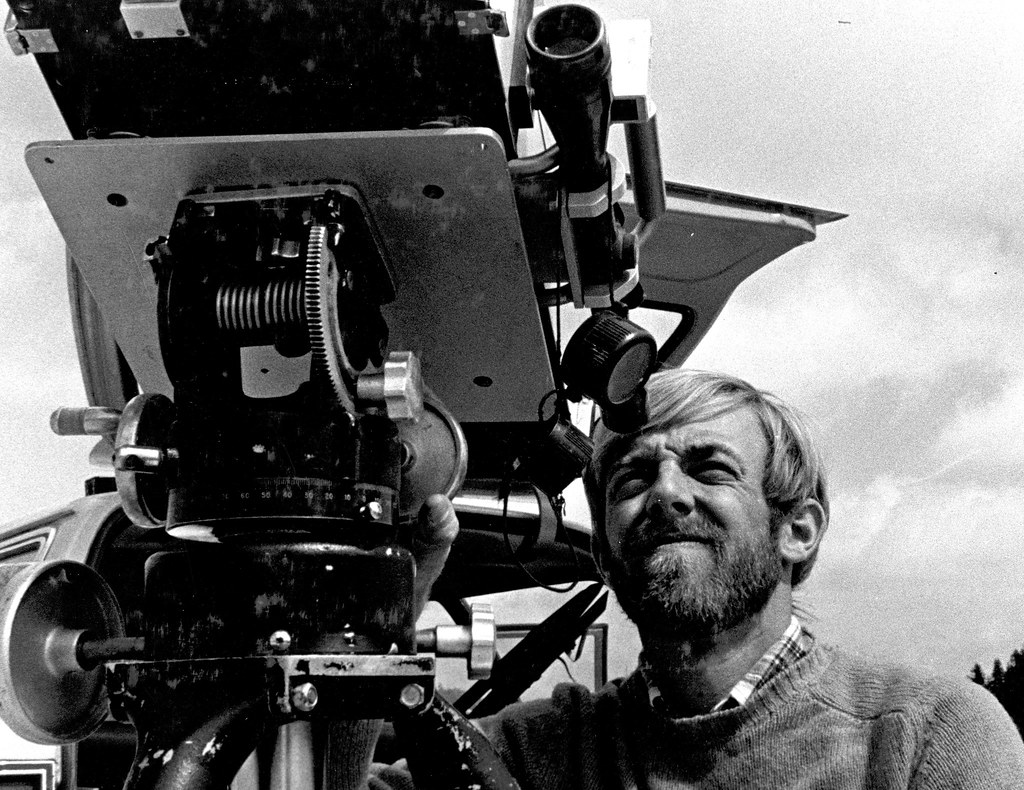

“They said, ‘Hey, we need help. We can’t do this on our own.’ And we said, ‘Yep, we can do that,’” recalled Darrin Morgan, Boeing’s chief strategist for creating new aviation fuels.

As a major U.S. exporter that has dealings with over 150 countries, Boeing had worked with airlines in the development of more fuel-efficient aircraft and better flying practices. Now it helped form and lead the Sustainable Aviation Fuel Users Group (SAFUG). It currently represents 27 airlines that consume one-third of the world’s jet fuel.

This was a step completely outside the global reach of Boeing or the world’s airlines: New aircraft fuels that met greenhouse gas reduction targets had to be developed and tested to meet tough aircraft standards. They could not freeze and had to be powerful and safe enough to run standard jet engines and use existing fuel delivery systems. Another goal was that airline passengers would not sense any difference in performance.

“We were trying to create a new industry that does not exist in the way we need it to exist,” explained Morgan, a former financial expert who was brought into Boeing because he was familiar with biofuels.

Finding low-carbon biofuels that can meet the requirements of the airlines, environmental groups and governments has undergone a long, lumbering takeoff. But, he said, he sees it as a step that’s beginning to happen.

Advice has come from many places. Environmental groups, worried about the sources of new fuels, rejected proposals to make biofuels out of trees. They were particularly worried about destruction of rainforests to create palm oil plantations. Social groups were unhappy about making advanced biofuels from food sources, such as corn, or on land used for food crops because a growing population will need more food.

Boeing and other SAFUG members also worked with another group. The Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB) was formed to include representatives of environmental, farm and social groups as well as experts from companies that make aircraft and jet engines. The idea was to forge a consensus for one standard of sustainability, not dozens.

“We sent a signal to the market very early that says we’re going to set a high bar. We said, ‘Folks, if you want to serve our industry, you need to meet that high bar,’” explained Morgan.

ENTER THE FINNISH PIONEER

There is a lot at stake in this.

Airlines produce about 2 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases. If the industry does not succeed in reducing its emissions, they are expected to grow to 3 percent by 2050.

In retrospect, Morgan thinks that the peculiarity of the airlines’ dilemma turned out to be an asset in drawing support for clear standards and new ideas.

“That was the beauty of not having an incumbent industry. There was none for biofuels, so we could make it the way we wanted from the beginning.”

Flight tests that followed showed that some of the most promising results came from Neste Corp., a company that was formed in 1948 as the state-owned petroleum company for Finland. In 2005, it became focused on a process that made diesel fuel using fatty acids and oily agricultural residues that included palm oil.

There was a large market for cleaner fuels in Europe, and Neste soon dominated it, making diesel used for trucks and cars. After being attacked by Greenpeace and other environmental groups, Neste began to modify its process. It agreed to phase out the use of palm oil, which is used for a variety of foods, and rely mainly on non-edible vegetable and animal wastes and residues to make what the company calls a “hydrotreated vegetable oil,” a product that closely resembles kerosene.

Working with Boeing and other members of the RSB, Neste came up with what is called a “drop-in” fuel that can be used in jet and turboprop engines. So far, according to Neville Fernandes, general manager for Neste in the United States, it has been successfully tested in 1,200 commercial flights.

What makes Neste’s fuel different from other competitors in the race to develop a bio-jet fuel is that the company already operates two refineries that make biodiesel for it, so it can quickly scale up and produce much larger quantities of jet fuel that can, according to the company, cut an airliner’s greenhouse gas emissions from 40 to 90 percent.

“It is definitely fair to say that Neste is a pioneer,” explained Boeing’s Morgan. “They took a big risk and deserve a lot of credit. They bet a large percentage of their company on the future of renewable fuels at a time when a lot of people were not making that bet.”

The hurdle that remains is called ASTM International. It was formed in 1898 as the American Society for Testing and Materials, and its first decision was to approve the steel used for rails by the Pennsylvania Railroad. It has since become international and has offices around the world that help set health, quality and safety standards for over 12,000 products.

Boeing and other aircraft and jet engine manufacturers have formed an ASTM committee to decide whether the fuel from the Neste process can be used globally for making low-carbon jet fuel.

THE END OF “BIOFUELS 1.0”

If ASTM approves, then the pool of renewable jet fuel will grow from a tiny 2 million gallons to a potential 2 billion gallons annually.

That’s not nearly enough to fuel the entire global airline industry, but, as Morgan explains, “it’s really an important step because it gets us out of the experimental phase and gets industries into large quantities at cost-competitive prices.”

An enlarging market, he hopes, will encourage more oil refiners and other companies to get into the business. It will also mark the end of what Morgan calls “Biofuels 1.0,” a risky period for governments, innovators and investors who assumed low-carbon jet fuels were a venture that would promptly take flight. Unlike Neste, several companies that have tried to make biofuels have crashed into bankruptcy. Others have made sudden shifts into products that don’t have to fly.

One of these survivors is Cool Planet Energy Systems, a Greenwood Village, Colo., firm that made a splash in 2009 with a technology called pyrolysis that can heat farm wastes, wood chips and nutshells in the absence of oxygen to create fumes that are then passed through a catalyst to make a liquid biofuel. “You don’t have any further refining or upgrading processing. It’s a ready to use liquid fuel. You just have to blend it together,” explained Wes Bolsen, the head of business development for Cool Planet.

The process also resulted in a dirtlike waste called char.

According to Bolsen, the process attracted investments from three major oil companies and won a $91 million grant from the Department of Agriculture. The potential feedstocks to be used by the company to make renewable jet fuel seemed unlimited.

“There are 42 million acres of beetle-killed trees in the northern Rockies. Those trees are going to fall down and rot and turn into methane, which is much worse than carbon dioxide,” he said, noting that by turning wood chips into biofuel, his company would actually be reducing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

Cool Planet built a pilot plant that worked, but it never got to the point where it could begin selling a biofuel. Its investors balked at raising the hundreds of millions it needed to build the first commercial-sized facility.

“The hardest thing to do is to get the first commercial-scale plant. It will be the most inefficient plant ever built because you’re going to learn from it,” explained Bolsen.

To stay in business, the company quickly needed a product to sell, so it turned to the char, the waste left over from pyrolysis. The char was branded “Cool Terra,” which the company describes as “an engineered biocarbon designed to improve soil health.” It is a soil additive that Cool Planet now markets in 48 states.

According to Bolsen, it has become popular with golf courses and nurseries that grow tomatoes and strawberries.

Cool Planet says it has raised $30 million and is building a plant in Louisiana that is designed to produce the char. Bolsen explained that it may not be ready to carry out the company’s dream to produce a biofuel. “You’ve got to do this step-wise,” he said.

Another survivor that managed a soft landing was Solazyme, a San Francisco startup that developed a biofuel from algae and sugar that seemed to hold promise until the company’s stock price began to crash last year. Then it transformed itself into a company called TerraVia Holdings Inc., which sells algae-based oil for cosmetics and food products.

At least a half dozen companies followed the trajectory of KiOR, a high-flying Pasadena, Texas, company that took off in 2007, briefly enjoyed a valuation of $1.5 billion for its process to turn wood chips into biofuels, failed to live up to its production estimates, and then crashed into a messy bankruptcy in 2014.

Then the attorney general of Mississippi—selected as the home of KiOR’s first commercial plant—called it “one of the largest frauds ever perpetrated on the state of Mississippi.” But others survived to meet the next challenge.

Reprinted from Climatewire with permission from E&E News. E&E provides daily coverage of essential energy and environmental news at www.eenews.net.